The Ben Franklin Awards

Once a year, bioinformatics.org gives the “Benjamin Franklin” award to a person whose practice has “advanced open access in data and methods for life sciences.” There’s no cash prize, and the recipient doesn’t even get to give a talk. It usually gets presented in the 15 minutes before the (already early) 8:00am morning keynote sessions at the Bio-IT World conference. I’ve missed more of the awards ceremonies than I’ve attended because of the early hour.

I became a member of bioinformatics.org back in 2002 – the first year of the award. If I remember right, I signed up after meeting the founder, Jeff Bizzaro at some now-defunct conference. It might have been one of the O’Reilly Bioinformatics junkets, or maybe one of the IDG ones … perhaps ClusterWorld. Jeff was doing the legwork of building an organization, convinced me the award was a good idea, and got me signed up with a free membership.

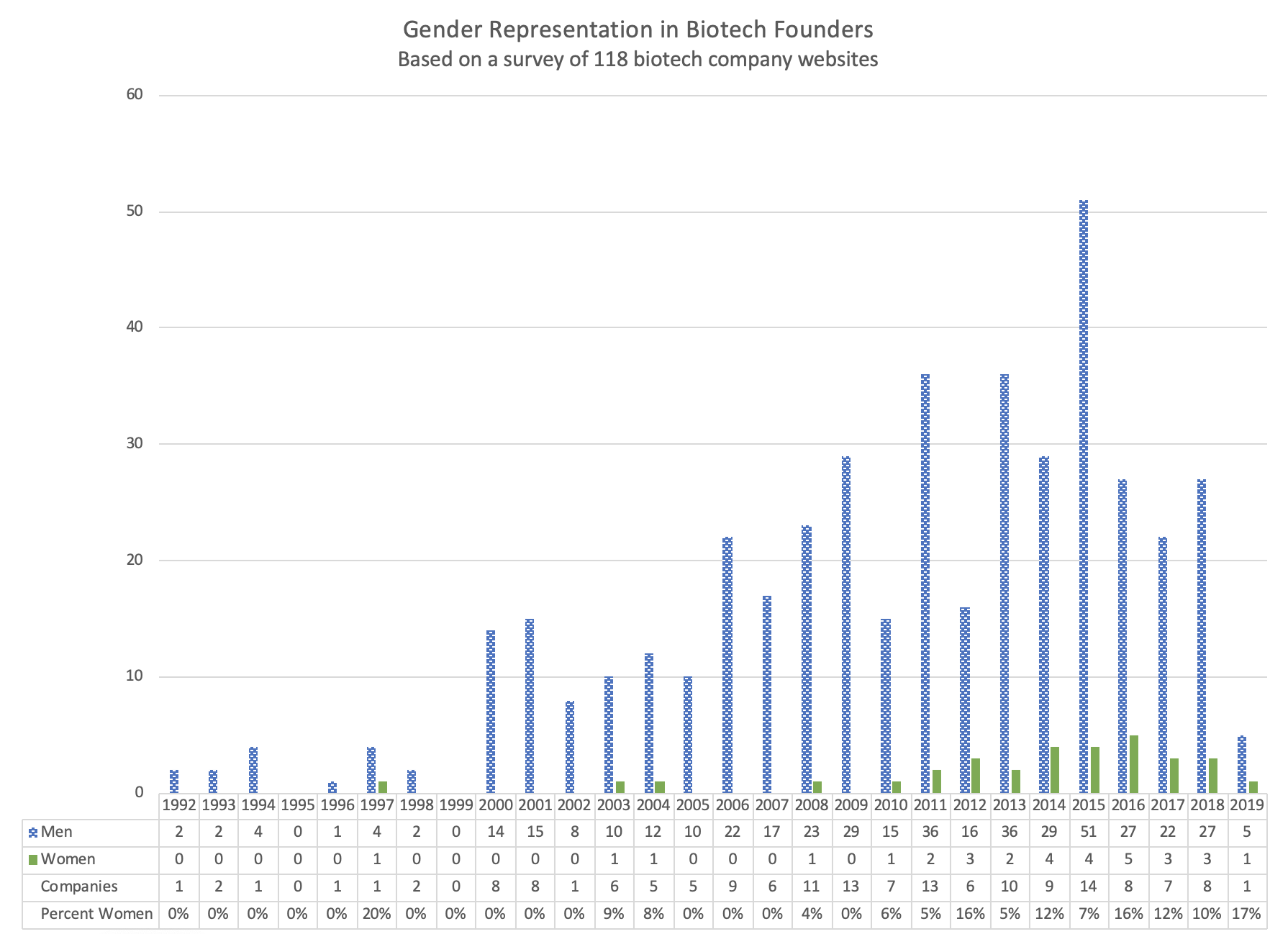

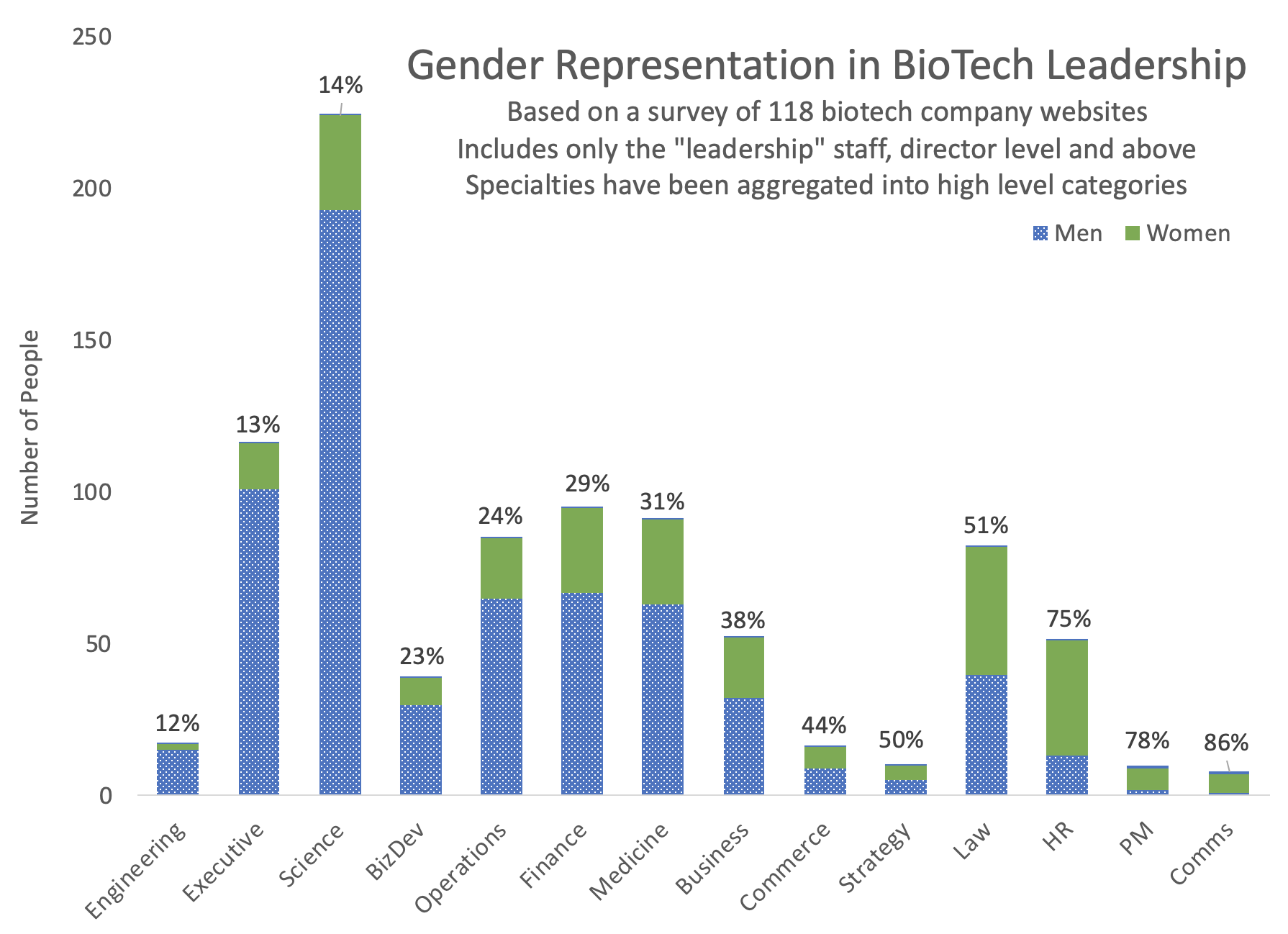

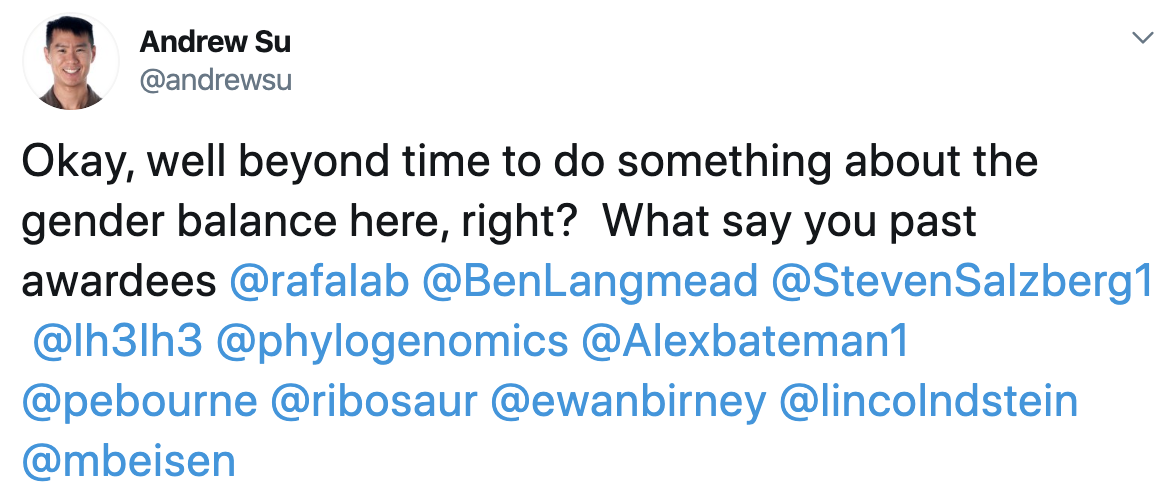

Last Friday, Andrew Su (@andrewsu) pointed out on Twitter that 17 out of 18 of the Franklin awards have gone to men. He called on the prior recipients to “do something.”

Jonathan Eisen (@phylogenomics), who received the award in 2011, reminded us that he had come to the same realization half a year [edit: actually quite a while] earlier. Eisen took the award off his wall and memorialized the deed on Twitter with a blank-spot-on-the-wall selfie back in May.

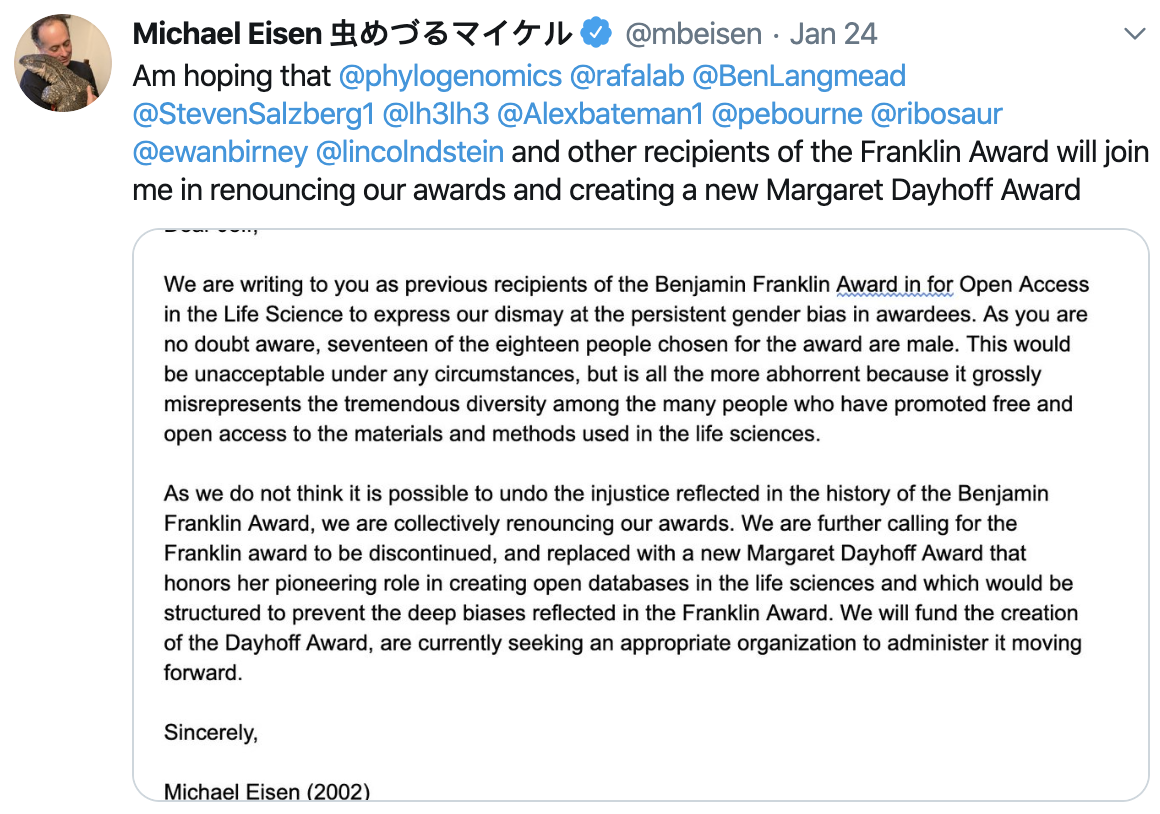

Michael Eisen (@mbeisen – the 2002 recipient, not to be confused with Jonathan, above) went further and used some pretty strong language to demand that the award be closed down as a bit of accountability for the “injustice reflected in [its] history.”

My opinions on this are below, but first I want to share a couple of stories from a parallel universe – the world of awards given to science fiction authors.

Sad Puppies

Until late last year, the “John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer” was an annual thing. Then the 1999 winner, Jeannette Ng, pointed out in her acceptance speech that John Campbell was a noted fascist and a truly odious human being by modern standards.

In the space of about two weeks, the sci-fi community basically said “huh, about that, oh wow, um, yeah – good point, –awkward-, how about if we change the name?” Thus was born the “Astounding” award for best new writer, after the grand old “Astounding Science Fiction” magazine.

Speaking up makes a difference. Jeannette Ng did a good thing.

The sci-fi community has done a lot of this sort of work in recent years. In 2015 through 2017, a right-wing, anti-diversity group, organized under the name “Sad Puppies” saturated the nominations for another venerable award (the Hugos). Fortunately, the community came together and a majority of voters chose “no award” rather than support the puppy’s biased agenda.

Neither of these situations is a great model for what’s going on with the Ben Franklin award. The name isn’t the problem – Franklin was a noted curmudgeon and was certainly a product of his era, but his name and writings are not generally associated with oppression and inequity. Similarly, I’m not aware of any puppy-orthologs who are suborning bioinformatics.org or manipulating the nominations.

Don’t Blame the Mirror

I have huge respect for both Michael and Jonathan’s scientific and public advocacy work, and I hesitate to second guess either of them – let alone both at the same time. Still, I can’t get around the fact that if we don’t like what we see when we look in the mirror, taking the mirror down is not going to improve the situation.

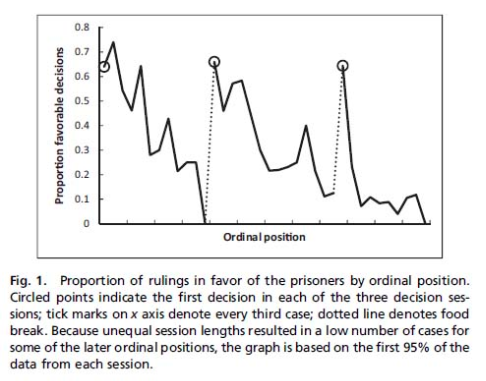

I think that throwing the Ben Franklin award under the bus as if it had actively perpetuated bias and sexism misses a subtle point. This was a sin of omission, of failing to compensate effectively, rather than a sin of commission. This is a common story – people and systems that fail to take pre-existing bias into account wind up perpetuating it. It is, in fact, the mechanism by which good and decent people become complicit in woefully biased organizations.

My experience is that this sort of public punishment of sins of omission tends to drive decent people away from advocacy. This acts to push the community in the wrong direction, away from engagement rather than towards it.

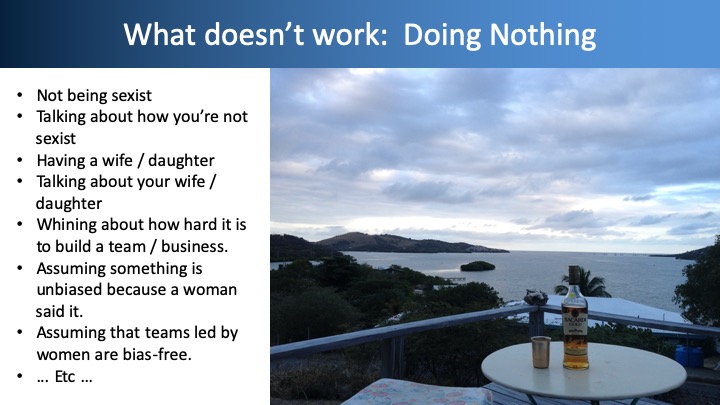

I’ve written about why men hesitate to speak up, and it’s nasty stuff. I also spoke at a recent meeting of the Rosalind Franklin Society about my own challenges in engaging with my well-intentioned but bias-perpetuating colleagues without simply losing friends and cutting myself out of the conversation.

What Should We Do Instead?

We’ve got a ways to go before we’re anywhere close to the high bar set by the community of science fiction authors and fans, but we can take steps. I think that we should modify the award rather than nuking it and shaming the organizers.

My vote is for bioinformatics.org to carry on with the Franklin award, but to modernize the selection process to prevent it from merely continuing to reinforce and amplify bias. The necessary changes from my perspective are (a) insist on a credibly diverse pool of nominees before allowing a vote (which Jeff B. and Bio-IT World should perhaps have been doing all along) and (b) include the possibility of a “no award” vote as a fail safe against a sad-puppies style vocal minority messing things up. Coupled with advocacy and engagement from senior members of the community to nominate and sponsor worthy people who might not yet be household names, we might see the numbers start to change in a relatively short time.

At the same time, yes, let’s create new awards. Let a thousand flowers bloom, and let them be named for Dayhoff and other frequently overlooked pioneers. Let’s just not miss the opportunity to take a clear-eyed look at what drove these biased results, and think about how we can steer the community so that we’re not having the same conversation 20 years from now.