I posted a quick tweet this morning about the state of data in health care.

Over the years, I’ve worked with at least half a dozen projects where earnest, intelligent, diligent folks have tried to unlock the potential stored in mid to large scale batches of electronic medical records. In every case, without exception, we have wound up tearing our hair and rending our garments over the abysmal state of the data and the challenges in getting access to it at all. It is discordant, incomplete, and frequently just plain-old incorrect.

I claim that this is the result of structural incentives in the business of medicine.

What is a Medical Record?

Years ago the medical record was how physicians communicated amongst themselves. The “clinical narrative” was a series of notes written by a primary care physician, punctuated by requests for information and answers from specialists. Physicians operated with an assumption of privacy in these notes, since patients didn’t generally ask to see them. Of course they were still careful with what they wrote. If things went sideways, those notes might wind up being read aloud in front of a judge and jury.

In the 80’s, electronic medical records (EMRs) added a new dimension to this conversation. EMRs were built, in large part, to support accurate and timely information exchange between health care organizations and “payers” including both corporate and government insurance. EMRs digitized the old clinical narrative basically unchanged. They sometimes allowed in-house lab values to be transferred as data rather than text, though in many cases that sort of feature came much later. Most of the engineering effort went into building a framework for billing and payment.

The savvy reader will note that neither of these is a particularly good way to build a system for the collection of patient data. Instead, we’re dealing with risk avoidance.

A Question of Risk and Cost

Being the Chief Information Officer (CIO) of a health care system or a hospital is a hard, stressful, and frequently thankless job. Information Technology (IT) is usually seen as a cost center and an expense rather than as a driver of revenue. A savvy CIO is always looking for ways to reduce costs and allow their institution to put more dollars directly into the health care mission. Successful hospital CIOs spend a lot of time thinking about risk. There are operational risks from attacks like ransomware, compliance risks, risks that the hospital will expose patient data inappropriately, financial risks from lost revenue, legal risks from failing to meet standards of care, and many more.

These pressures lead to a very sensible and consistent mindset among hospital CIOs: They have a healthy skepticism of the “new shiny,” an aversion to change, and a visceral awareness of their responsibility to consistent and compliant operations

So physicians are incentivized to avoid litigation, hospital information systems are incentivized to reduce exposure, and the core software we use for the whole mess is written primarily to support financial transactions.

Every single person I’ve ever met in the business and practice of health care, without exception, wants to improve patient lives. This is not a case where we need to find the bad, the malevolent, or the incompetent people and replace them. Instead, it’s one of those situations where good, smart hardworking people are stuck with a system that we all know needs a solid shake-up.

That means that when someone (like me) shows up and proposes that we change a bunch of hospital practices (including modifying that damn EMR software) so that we can gather better data, it falls a bit flat. If I reveal my grand plan to take the data and use it for some off-label purpose like improving the standard of care globally, I am usually politely but firmly shown the door.

But it gets worse.

Homemade Is Best

Back in the bad old days, it was possible to convince ourselves that observations made by physicians were the best and only data that should be used in the diagnosis of disease. That’s demonstrably untrue in the age of internet connected scales and wearable pulse and sleep monitors. I’ve written before about the reaction I receive when I show up to my doctor as a Patient With A Printout (PWP). Even here in 2019, there are not many primary care physicians who are willing to look at data from a direct to consumer genetics or wellness company.

The above isn’t strictly true. I know lots of physicians who have a very modern approach to data when we talk over coffee or dinner. However, at work, they have to do a job. The way they are allowed to do that job is defined by CIOs and hospital Risk Officers who grow nervous when we try to introduce outside data sources in the clinical context. What assertions do we have that these wearable devices meet any standards of clinical care? Who, they might ask, will be be legally responsible if a diagnosis is missed or an incorrect treatment applied?

So we’re left with a population health mindset that says “never order a test unless you know what you’re going to do with the result,” except that in this case it’s “don’t look at a test that was already done, you might wind up with an inconvenient incidental finding, and then we’ll have to talk to legal.”

Health systems incentivize risk avoidance above more accurate or timely data. They do this because they are smart, and because they want to stay in business.

So we collect information with a system tuned for billing, run by people whose focus is on risk avoidance. Is it any wonder that when we extract that data, what we find is a conflicting and occasionally self-contradictory mess?

There’s no incentive to have it any other way,

A Better Way

Here in 2019, most people who pay attention to such things believe that data driven health insights will lead to better clinical outcomes, better quality of life, lower overall costs for health care, and many other benefits.

Eventually.

One ray of hope comes from the online communities that spring up to connect people with rare and terrible diseases. These folks share information amongst friends, family, researchers, and physicians as they search desperately for any hope of a cure. Along the way, they create and curate incredibly valuable data resources. The difference between these patient centric repositories and any extraction that we might get from an EMR is simply night and day.

A former colleague was fond of saying, “a diagnosis of cancer really clarifies your thinking about the relative importance of data privacy.”

Put another way: If we put the patient at the center of the data equation, rather than payment, we’re really not that very far from a much better world – and all those wonderful technologies I mentioned will suddenly be quite useful.

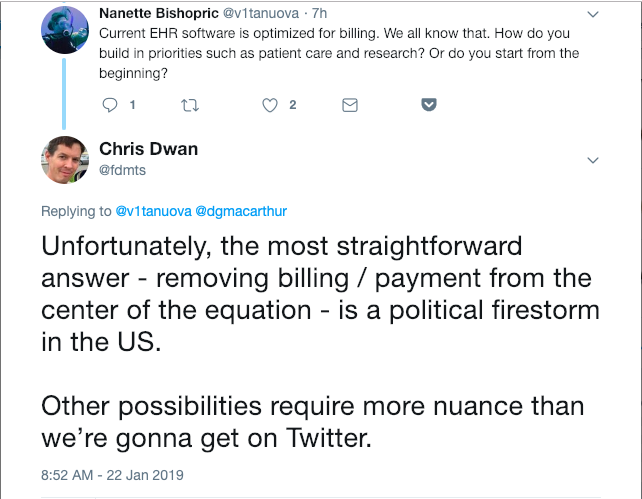

Unfortunately, that’s a political question these days:

So where do we go from here? I’m not sure.

I do know for certain that -merely- flinging the messy pile of junk against the latest Machine Learning / Artificial Intelligence / Natural Language Processing software, without addressing the underlying data quality, is unlikely to yield durable and useful results.

Garbage in, garbage out – as the saying goes.

I would love to hear your thoughts.

This is all eminently sensible. How does this relate to the recent piece by Atul Gawande (https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/11/12/why-doctors-hate-their-computers) “Why Doctors Hate Their Computers” – he doesn’t hint that the EMR info that is being entered is driven by billing / financial / risk avoidance, just that it is messy / isn’t working for individual doctors. It seems like what you’re describing could be considered “root-cause” of the problems Gawande is describing.

This paragraph in particular jumps out at me as being related to your point about PWP:

““Step counts!” Malhotra said. “Oh, if we just had step counts.” His wheels were turning. What if they made a tab in the electronic medical record with whatever data on activity patients were willing to provide?”

I’ve got huge respect for Dr. Gawande. His article echos a sentiment I’ve been hearing my entire life from family and friends in the business of medicine.

The information tools and processes in health care are funded, built, and maintained based on business priorities. Ease of use for physicians and patient-centric data management are not high on the list.

Part of the problem is the hero-culture among physicians. Their training emphasizes the need to accept that the practice of medicine is a terrible burden that, done correctly, consumes your entire life. Frankly, they put up with stone age information systems long after the rest of us would have mutinied and demanded better.

Chris – I really enjoyed this blog post, and despite agreeing with much of it, I found myself heartbroken by the post as well. The early proponents of health information technology cited the ways in which IT revolutionized other industries, like banking. But other than streamlining billing and making it easier for physicians like myself to sort through patient documentation, EMRs haven’t yet led to the revolution that we dream of.

Billing is obviously always going to be a big part of any healthcare system, but I wonder if there are healthcare systems that you have encountered that seem more amenable to gathering quality data and analyzing it. Boston, with a largely fee-for-service environment and high concentration of tertiary care hospitals, doesn’t seem like the right place to look. I wonder if a place like Kaiser Permanente (integrated, largely capitated model) might have better luck. Or the UK.

I share your frustration and heartbreak.

I hear that Estonia has a pretty solid system of medical informatics. I don’t have firsthand experience, but we collaborated with their national biobank at a prior job and it was an impressive setup from the outside.

Similarly, the UK Biobank was a huge investment that is starting to pay massive dividends.

In the US, I have a certain amount of hope for the NIH’s “All of Us” effort, though it’s been slow slow slow and plagued by politics.

I wonder how much systems like Epic play into this — I’ve started seeing a few comments around DMCA-style takedowns of EPIC screenshots, and they seem to be the only player in this particular game (at least that’s of any note).