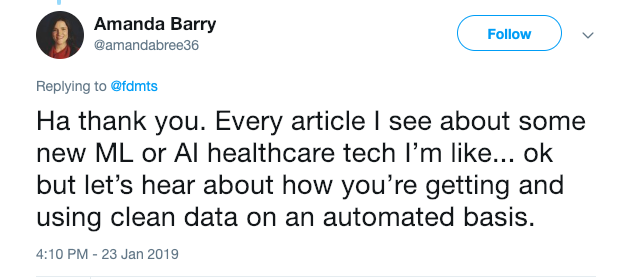

In my previous blog post, I talked about the fact that medical records are a dumpster fire from a scientific data perspective. Apparently this resonated for people.

This post begins to sketch some ideas for how we might start to correct the problem at its root.

Lots of people have thought deeply about this stuff. One specific example is the Apperta Foundation whose white paper makes a wonderful introduction to the topic.

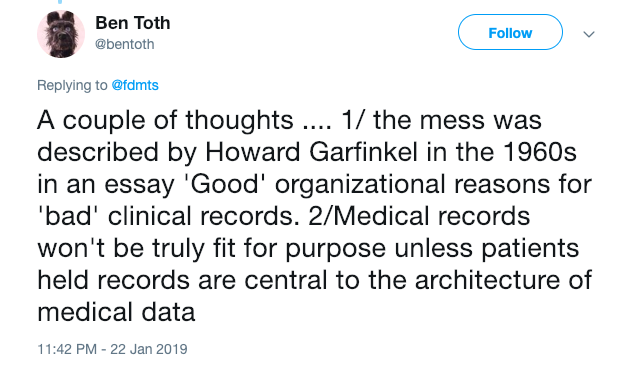

@bentoth’s second point, above, is exactly correct. Until we put the patient at the center of the medical records system, we’re going to be digging in the trash.

The question is how we get from here to there.

Not Starting From Zero

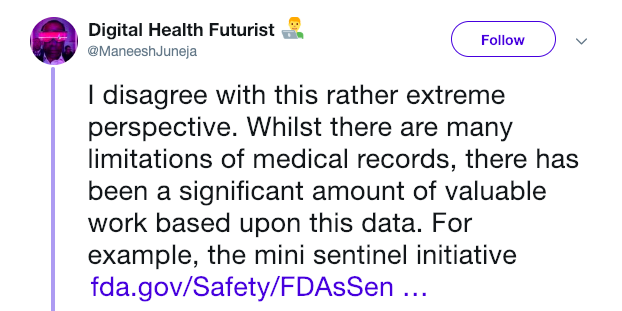

Before digging in, I want to address a very valid objection to my complaint:

It’s true: Even given the current abysmal state of things, researchers are still making important discoveries. This indicates to me that it will be well worth our while to put some time and effort into improving things at the source. If we can get value out of what we’ve got now, imagine the benefits to cleaning it up!

Who Speaks for the Data?

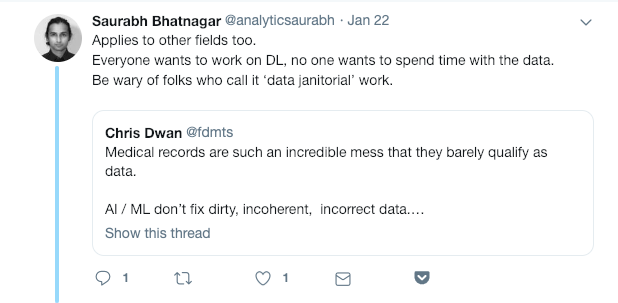

One of the first steps towards better data, in any organization, is to identify the human beings whose job is, like the Lorax, “speak for the data.” Identifying, hiring, and radically empowering these folks is a recommendation that I make to many of my clients.

Just … please … don’t call them a “data janitor.”

If you tell me that you have “data janitors,” I know that you consider your data to be trash. Beyond that, I also know that you consider curation, normalization, and data integration to be low-respect work that happens after hours and is not part of the core business mission. It’s not a big jump from there to realize that the structures and incentives feeding the problem aren’t going to change. Instead, you’re just going to hire people to pick through the trash and stack up whatever recyclables they can find.

I’ve even heard people talk about hiring a “data monkey.” Really, seriously, just don’t do that, even in casual conversation. It’s not cool.

Who does the work?

It takes a huge amount of work to capture primary observations, and still more effort to connect them to the critical context in which they were created. Good metadata is what allows future users to slice, dice, and confidently use datasets that they did not personally create.

Then there is the sustained work of keeping data sets coherent. Institutional knowledge and assumptions change and practices drift over time. Even though files themselves may not be corrupted, data always seems to rot unless someone is tending it.

This work cannot simply be layered on as yet another task for the care team. Physicians and nurses are already overwhelmed and overworked. Adding another layer of responsibility and paperwork to their already insane schedules will not work.

We need to find a resource that already exists, that scales naturally with the problem, and who also has a strong self-interest in getting things right.

Fortunately, such a resource exists: We need to leverage patients and their families. We need to empower them to curate and annotate their own medical records, and we need to do it in a scalable and transparent way.

I’m willing to bet that if we start there, we’ll wind up with a population who are more than happy, for the most part, to share slices of their data because of the prospective benefits to people other than themselves.

The tools already exist

Health systems don’t encourage it, but patients can and do demand access to the data derived from their own bodies. People suffering from rare or undiagnosed diseases make heavy use of this fact. They self-organize, using services like Patients Like Me or Seqster to carry their own information back and forth between the data silos built by their various providers and caregivers. Similarly, physicians can work with services like the Matchmaker Exchange to find clues in the work of colleagues around the world.

Unfortunately, there is no easy way for this cleaned and organized version of the data to get back into the EMR from which it came. That’s the link to be closed here – people are already enthusiastically doing the work of cleaning this data. They are doing it on their own time and at their own expense because the self-interest is so clear.

The job of the Data Lorax is to find a way to close that loop and bring cleaned data back into the EMR. This is different from what we do today, so we’re going to need to adapt a lot of systems and processes, and even a law or a rule here or there.

Fortunately, it’s in everybody’s interest to make the change.